Improving Occupational Health and Safety Compliance in Pakistan: Lessons from Southeast Asia

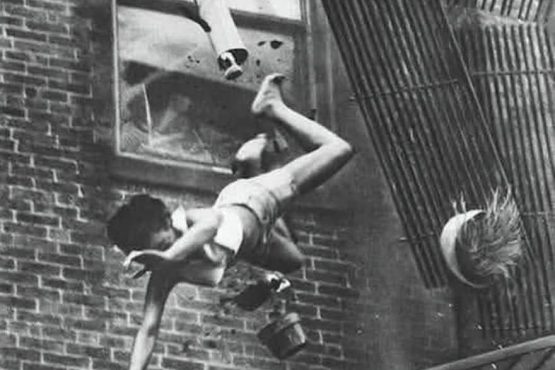

Pakistan’s industrial landscape ranges from sprawling garment factories and steel mills to small workshops and a huge informal sector. As tragedies like the 2012 Baldia Town factory fire—in which 260 workers died after an exit was locked—and recent boiler explosions show, poor occupational health and safety (OHS) practices continue to claim lives. Pakistan has ratified 36 International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions, but still has not adopted key OHS instruments such as Convention 161 on Occupational Health Services and Convention 176 on Safety and Health in Mines[1]. Reliable data on workplace accidents is scarce because there is no centralised reporting system; the ILO estimates that 1,136 injuries occur per 100,000 workers annually, a figure widely regarded as an under‑estimate[2]. Frequent accidents—ranging from mine collapses to factory boiler explosions—underscore how far Pakistan lags behind regional peers in OHS compliance[3].

The state of OHS compliance in Pakistan

Pakistan’s federal Occupational Safety and Health Act 2018 and various provincial laws (Sindh 2017, Punjab 2019/2022, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 2022) provide a legal framework. Yet enforcement is weak. Inspection systems are under‑resourced, employers view safety as a cost rather than an investment, and most workers are not aware of their rights. Much of the economy operates informally; unregistered factories escape scrutiny altogether. Many buildings lack fire exits and basic safety equipment. The 2012 Baldia factory fire and a series of 2024–2025 boiler explosions illustrate systemic failures[3].

Stay Connected

Similar Articles

To address these issues, experts at a recent national conference urged Pakistan to modernise labour laws, ratify outstanding ILO conventions, and adopt a national OHS policy. They called for a robust inspection system, awareness campaigns for employers and workers, capacity‑building for regulators, incentives for safer technology, and stricter penalties for violators[4]. Such proposals remain largely on paper, but a few initiatives show promise.

The Pakistan Accord

The Pakistan Accord on Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry—an extension of the Bangladesh Accord—illustrates how binding agreements can drive compliance. Launched in 2023, the Accord brings together brands, unions and local manufacturers. By August 2024, safety inspectors had conducted fire, electrical and structural audits at 185 factories in Karachi, Lahore and Faisalabad, identifying more than 5,500 safety issues[5]. Immediate actions included reducing loads on overstressed columns and shutting down unsafe electrical panels[6]. Corrective action plans have been published for 30 factories, promoting transparency[7]. Although this programme covers only a fraction of Pakistan’s factories, it demonstrates that enforceable agreements with buyer pressure can compel suppliers to invest in safer infrastructure.

Learning from Bangladesh

Pakistan’s garment sector competes directly with Bangladesh’s, where the Bangladesh Accord (2013–2018) transformed workplace safety following the Rana Plaza collapse that killed more than 1,130 workers. The Accord conducted 66,000 safety inspections, achieving a 92 % remediation rate, and trained over 2.5 million workers on fire, electrical and structural safety[8]. Its complaint mechanism addressed 1,681 grievances, and women played a significant role: 6,046 women served on factory safety committees and 1.6 million women were trained[9]. The International Accord has since been extended to Pakistan; however, progress remains modest, with 223 women on safety committees and around 2,000 women receiving training[10]. The contrast underscores the need for scale and genuine collaboration among brands, unions and local authorities in Pakistan.

Regional comparisons: Southeast Asia’s reforms

While Pakistan grapples with fragmented laws and weak enforcement, several Southeast Asian countries are modernising their OHS regimes. Their experiences offer instructive lessons.

Malaysia: comprehensive amendments and tougher penalties

Philippines: universal health care and strict reporting

Thailand: comprehensive safety officer regulations

Indonesia: national programmes and sector‑specific codes

Lessons for Pakistan

While Pakistan grapples with fragmented laws and weak enforcement, several Southeast Asian countries are modernising their OHS regimes. Their experiences offer instructive lessons.

1. Broad coverageof all workplaces

2. Clear duties and empowered workers –

3. Stricter penalties and liability –

4. Data‑driven oversight and mandatory reporting –

5. Training and professionalisation of safety roles –

Thailand mandates full‑time safety officers with prescribed qualifications and training[24], while Malaysia requires employers to appoint OHS coordinators[15]. Pakistan should professionalise safety roles, ensuring that factories have trained officers who can enforce standards.

6. Integration with health services –

7. Sector‑specific codes and international cooperation –

The way forward for Pakistan

Pakistan’s government, employers and worker organisations must move beyond rhetoric and adopt concrete measures. Ratifying ILO Conventions 161 and 176 would signal commitment. A national OHS authority could harmonise provincial laws, collect data and enforce standards. The government should adopt Malaysia‑style amendments to broaden coverage and strengthen penalties, and follow the Philippines in linking OHS compliance to universal health coverage and mandatory reporting. A comprehensive training and certification programme for safety officers, modelled on Thailand’s regulations, would professionalise safety roles across industries. Finally, Pakistan should expand the Pakistan Accord beyond the garment sector, replicate Bangladesh’s worker‑centric inspections, and encourage multinationals to require compliance in their supply chains.